Photos

Related Publications | Recognition and Accolades

Storming" the Beach: The Tenth Army lands at Higashi Beach on April 1, 1945. The Japanese 32nd Army allowed the Americans to land unopposed, conserving its strength for the defense of the southern half of the island.

Location, Location, Location: As this cartoon originally published in The New York World Telegram recognizes, Okinawa was an important strategic site because of its proximity to many significant areas in Asia and the Pacific. A force stationed on the island could stirke in any number of directions. American forces invaded Okinawa to use it as a forward staging area for the coming assault on Japan. Lt. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner, Jr., commanding officer of the Tenth Army, advocated retaining possession of the island after the war under some type of special legal status. The United States could use its control of Okinawa, Buckner argued, to contain Japan, Russia, or any other power that attempted to advance into the South Pacific area.

Slow Advance: Infantry elements of the XXIV Corps carefully move south. On April 4, the Corps made contact with the first line of Japanese defensive fortifications. During the early days of the battle, the Japanese succeeded in actually turning back American soldiers.

Artillery Strike: The hilly terrain of southern Okinawa aided Japanese troops defending the island. The U.S. Army relied on artillery to destroy Japanese positions, which were heavily fortified to withstand American shelling.

Tank Warfare: Confronted with strong Japanese fortifications, the Tenth Army found American armor a valuable asset, relying heavily on tanks to provide powerful and accurate heavy fire power at the excellent Japanese defensive positions. Tanks were equipped with flame throwers were particularly effective in close combat.

Infantry Support: Tanks were vulnerable to Japanese suicide squads that would throw themselves and explosive charges under the lightly armored carriage. Tank units tried using a cluster of anti-personnel mines on the turrets to thwart these attacks, but most tankers preferred to work as part of an infantry-tank teams when they assaulted the Japanese front lines.

Quagmire: In May heavy rains turned trenches, foxholes and roads into mud slicks. The cold, clammy weather slowed down the advance of the Tenth Army, allowing the 32nd Army to escape after the Americans breached the last established line.

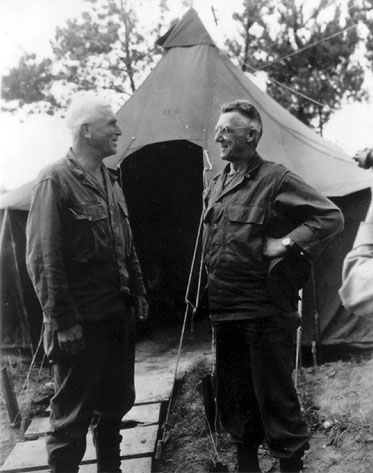

Seven Stars: Buckner and Gen. Joseph Stilwell confer in early June. Buckner commanded the Tenth Army, an amalgamation of Marine and Army units. Buckner never appreciated the differences in tactics between the two services. Stilwell was a harsh critic of Buckner during an inspection trip, and discussed with Gen. of the Army Douglas MacArthur removing him from command during the invasion of Japan. Ironically, Buckner was with Marines when he died in a Japanese artillery barrage as the battle neared an end, and Stilwell replaced him in command.

Stilwell on Okinawa: During Stilwell's inspection trip, he visited front-line units. Here he examines the progress of the 7th Infantry Division at a regimentalcommand post. "Seventh has no respect for the Japs," the General observed in his diary. His guide for a good part of his inspection was Maj. Gen. Archibald Arnold, commander of the division (left of map). This was a homecoming of sorts for Stilwell. At the start of the war, he was the commander of the division. In his diary, he noted: "Recognized everywhere and got friendly greeting."

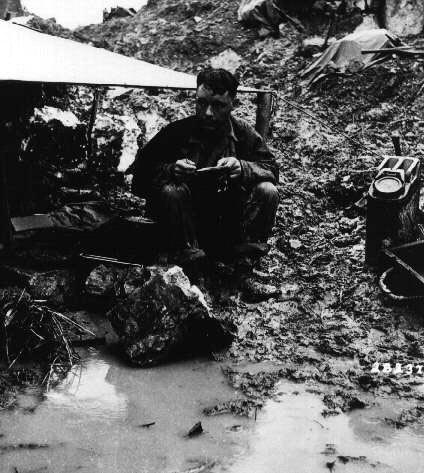

Two Generals in the Mud: Stilwell often had to travel on foot, because the thick mud immobilized most vehicles. He told the soldiers of the 96th Infantry Division the mud on Okinawa was the worst he had ever seen. "Mud is bad anyplace, but where caterpillars sink and spin their tracks, it's damn bad.

Two Samurai: Buckner's Japanese counterpart in command of the 32nd Army was Lt. Gen. Ushijima Mitsuru. Lt. Gen. Cho Isamu was his Chief-of-Staff. The two generals committed suicide in the traditional manner when the Americans smashed the last Japanese line of defense.

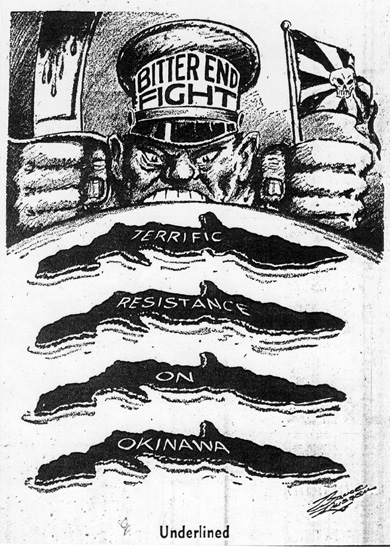

A Long Bitter Fight: In June, New York Herald Tribune correspndent Homer Bigart initiated a controversy when he published an article critical of Buckner's "ultra-conservative" tactics and his rejection of a proposal to launch a second landing on the southern tip of the island behind Japanese lines. Syndicated newspaper columnist David Lawrence used this accout to blame Buckner for the costly nature of the engagement, casting the second front issue into an Army-Marine dispute. Even though Bigart and the editorial board of the Herald Tribune criticized Lawrence for exageration, these charges of military incompetence have remained a major issue in the study of this battle. The editorial cartoons that follow show, to one degree or another, that the American public rejected these allegations against Buckner. This Los Angeles Times cartoon specifically assigns to the Japanese responsibility for the costly battle.

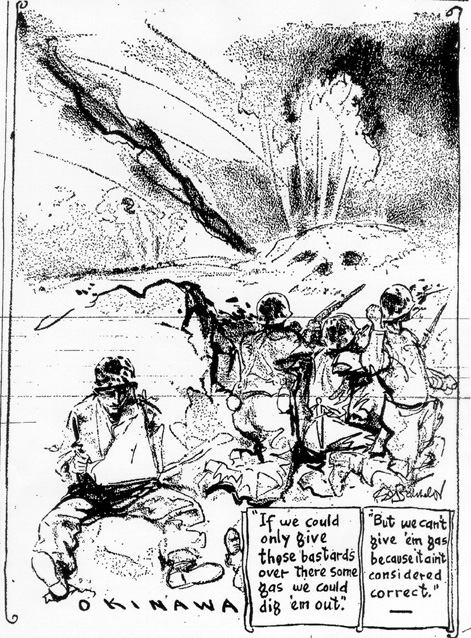

"Give 'em Gas": This editorial cartoon, published in the Washington Times-Herald, expressed frustration at the slow pace of the battle and restrictions that Americans placed on themselves that seemed only to prolong the struggle. No poison gas was used on Okinawa, but Stillwell sent a memo to Gen. of the Army George C. Marshall, U.S. Army Chief of Staff, recommending its use in the invasion of Japan.

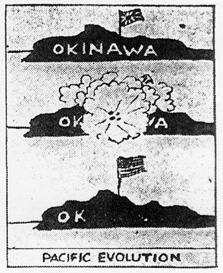

Target Secured: According to this cartoon that appeared in the Louisville Courier-Journal, victory on Okinawa, regardless of cost, was all that mattered in the end.

Fortress Okinawa: This editorial cartoon in the San Francisco Chronicle accurately summarized American thinking about Okinawa as a harbinger of the coming invasion of Japan.

Death of a Hero: When Buckner died it was front page, banner-headline news in papers across the country. He was the highest ranking American officer to die in the war, and with the victory in Europe, Okinawa was the focal point of the conflict. News of his passing came at the same time that Gen. of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower returned to the United States. This cartoon in Buckner's hometown paper, the Louisville Courier-Journal, made note of the ironic contrast in the fates of these two generals.

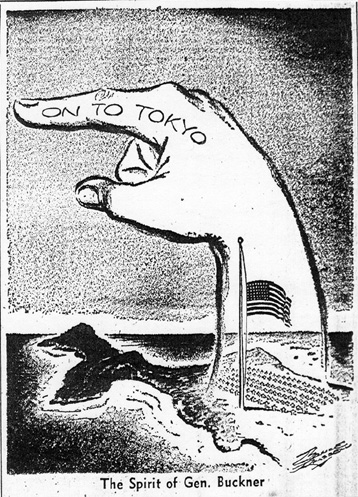

The Way of a Warrior Hero: A good example of how little impact the newspaper controversy had on Buckner's reputation is this cartoon in the Los Angeles Times.This drawing uses the memory of the martyred hero to call on the American people to stay focused on the next stage of the war. This sentiment was plausible, and keeping in character for Buckner.

The Last Surrender: On September 7, the Japanese garrison in the Ryukyus Islands surrendered to Stilwell and the Tenth Army. The formal capitulation of Japan took place aboard the U.S.S. Missouri three weeks earlier. The Ryukyus were the last element of the Emperor's military to end their resistance.

OCCUPATION

"Sign Here, Sir": In the early days of the American occupation, there were few recreational activities on Okinawa for either soldiers or their commanding general. Stilwell's diary indicates that letters from home and visiting entertainers were the only breaks from the monotony of life on the island. After a USO show in August 1945, Stilwell added his signature to the collection on the band's drum.

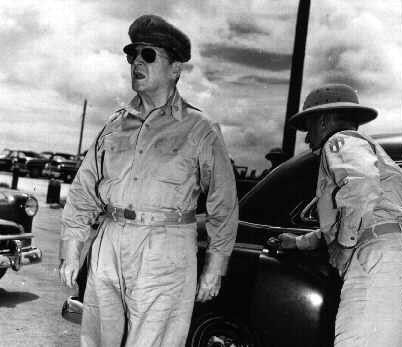

The American Shogun: Gen. of the Army Douglas MacArthur played a large role in breaching differences between various elements of the U.S. government on the issue of Okinawa. In 1948, he met with George F. Kennan of the State Department and explained that American retention of Okinawa allowed the U.S. to position itself to both protect and defend against Japan. State Department opposition to the retention of the island quickly ended after this meeting. Two years later in June, 1950, the general sided with the State Department against the Joint Chiefs of Staff on the issue of a Japanese peace treaty. He argued that the occupation had reached its limits, and American bases acted as protection for the Japanese, and a hedge against the resurrection of militant Japanese nationalism.

And Heads will Roll: Undersecretary of the Army Tracy Voorhees visits Okinawa on an inspection. Disturbed about reports of conditions on Okinawa, Voorhees visited the island in September, 1949. After the trip, a number of reforms and personnel changes took place. The military governor was replaced before the end of the month, and funding for the island increased dramatically.

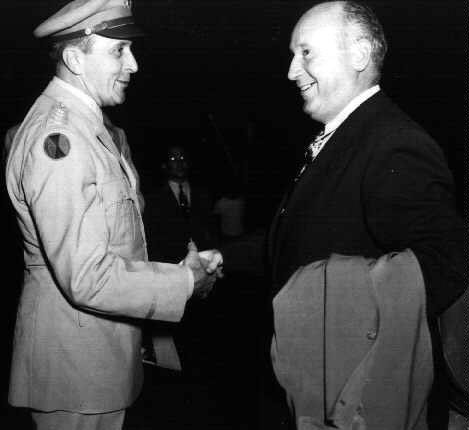

American Patron: Gen. Lyman Lemnitzer, Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Army Far East, greets Rep. Melvin Price of Illinois as he arrives in Tokyo. Price, a member of the House Armed Services Committee, showed a long interest in Okinawan issues. In 1955-56, he chaired a special subcommittee to investigate rental payments for American bases. In the 1960s, he sponsored legislation, which became known as the Price Act to provide economic aid to the island. He later worked to remove the maximum funding limit in this act.

Caraway v. Reischauer: Lt. Gen. Paul W. Caraway served as High Commissioner of the Ryukyu Islands from 1961 to 1964. Edwin O. Reischauer represented the United States from 1961-1966 as the ambassador in Tokyo. The two had several bitter confrontations over Okinawa. The ambassador wanted the island returned to Japan and favored allowing Japan to provide large sums of economic aid, while Caraway fought efforts to increase Japanese support, seeing it as the first step in striping the U.S. of what he considered the most vital base in the Pacific. Although Reischauer enjoyed favorable publicity during his tenure in Japan, his influence within the U.S. Government was generally limited to the bureaucracy within the State Department. Caraway had lengthy experience working at high levels of the U.S. government. He successful blocked the tepid efforts of the Kennedy White House to implement policy initiatives the ambassador, the Japanese government, and the State Department favored.

REVERSION

The Ultimate Bureaucrat: In 1966, President Lyndon Johnson appointed U. Alexis Johnson to serve as U.S. ambassador in Japan. The new ambassador started his career in pre-war Tokyo as a language officer, and was the senior officer in the Foreign Service at the time of his appointment. In previous years he had earned LBJ's respect and gratitude. As ambassador he negotiated the return of the Bonin Islands. While in Tokyo, he earned Richard Nixon's admiration and trust after providing standard VIP treatment to the former vice-president that Nixon often did not receive. When he became President, Nixon made Johnson the Undersecretary of State for Political Affairs, the fourth ranking position in the department. From this position, he conducted the final reversion negotiations.

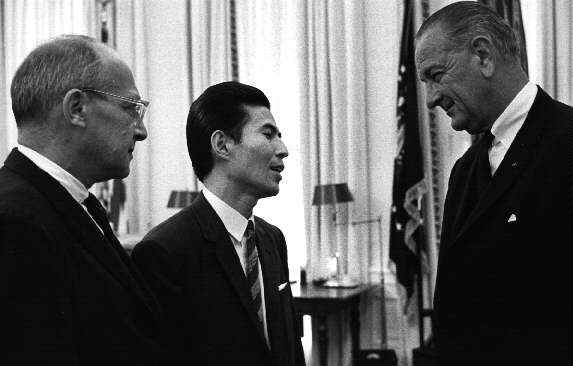

Secret Emissary: National Security Advisor Walt W. Rostow introduces Wakaizumi Kei to President Lyndon Johnson. Rostow and Wakaizumi were close friends and academic colleagues. Rostow was the godfather of Wakaizumi's son. Wakaizumi was also affiliated with Prime Minister Sato Eisaku's political faction. In 1967, Sato bypassed his foreign minister, a political rival, sending Wakaizumi to Washington to negotiate secretly with Rostow on the return of Iwo Jima.

The New Flag: The ensign that Okinawan fishing boats flew had become an emotional and difficult issue by the late Sixties. Okinawans wanted to fly the Japanese national flag, while American military officials opposed this idea, noting that Japan had no administrative authority for the island. Ambassador Johnson brokered a compromise that settled on this design. He made it clear that this new banner was not the national flag of Japan: they just looked alike.

Political Masters: Sato and Johnson privately discuss the return of Iwo Jima and the Bonin Islands in the Oval Office. Sato was telegenic, poised, and a master of political timing. He served eight years as prime minister the longest tenure in Japanese history. Johnson was a larger than life wheeler-dealer, best at assessing other people and making deals. While the two enjoyed cordial relations, both attempted to take as much as possible from the other, while giving as little as possible in return.

"Moving from one's positions now is filled with difficulties": The Okinawa issue was a problem for both Sato and Johnson according to this editorial cartoon in The Christian Science Monitor.

"Have a smoke": President Richard M. Nixon presents a package of Japanese cigarettes to Japanese Foreign Minister Kichi Aiichi in the Oval Office after agreement is reached on reversion. Kichi had vowed not to smoke again until Okinawa returned to Japanese control.

Agreement: Nixon and Sato at the White House on November 21, 1967, announce the reversion of the Ryukyu Islands. Each is flanked by their foreign ministers. Kichi is next to Sato, while Secretary of State William Rogers is on the right, next to Nixon. U. Alexis Johnson, in a position symbolic of his career, is above in the back row.

Return to Okinawa: The American Years, 1945-1972 Main Page